Fueling for runners part I: Which runs do I need to fuel for?

There are several essentials you’d never forget before going out to run: your shoes, your watch, and maybe your water bottle, too. These external things are important, yet all too often, we forget that for our training to be successful, we also need to focus on powering up from the inside out. In this first installment of a three-part series, let’s look at why you should fuel for every run, how to do so for different sessions, and what it can mean for your performance.

What happens if I don't fuel my run?

Runners often fall somewhere between those who are serious about pre-run fueling and those who don’t fuel at all. The former is great when it’s done right, while the latter can leave runners feeling depleted. Some common reasons runners skip pre-run fueling are:

- you don’t think you need it

- you are worried about GI distress

- you are busy and forget

- you don’t prioritize it

- your runner friends don’t fuel pre-run

- you think if you’re fasted, you’ll burn more fat

All of the factors discussed above contribute to many athletes shortchanging their potential progress and gains by not fueling. As we explored in a recent post, you need an ample supply of carbs to utilize as fast-burning fuel, first via glucose in your bloodstream and then from glycogen stored in your muscles and liver. The authors of a study published in the Journal of Sports Sciences wrote that “Carbohydrate availability is increased by consuming carbohydrate in the hours or days prior to the session, intake during exercise, and refueling during recovery between sessions.”

If you don’t check all three of these boxes, then you’re going to find it difficult to achieve your target pace and stick with it, might start to fatigue sooner, and will feel like you’re working harder than you should be. A position statement from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine stated that short-term low energy availability leads to decreased muscle strength, reduced endurance capacity, and a blunted response to training. On the mental side, inadequate fueling can also cause lack of focus, mood irregularities, and a loss of coordination that could increase your risk of injury. You probably wouldn’t plan to head out on a road trip if your gas tank was low or even empty, so why would you risk it with your own body?

Do I need to fuel before my short runs?

The thinking on short runs has typically been that your body has sufficient glucose and glycogen to power you through. But this is based on the premise that you’ve been eating optimally throughout the day and are coming into your training fresh and adequately fueled. The trouble is that you might not be, so if you’re starting from a calorie, carb, or energy deficit, things aren’t likely to go well. When you don’t have enough quick-acting glucose to power your shorter runs (or any activity, for that matter), you’ll need to tap into stored glycogen first and fat second, neither of which are as efficient. Think about the difference between putting small pieces of kindling on a fire versus loading a big log on top – one burns quickly while the other takes time to burst into flames and then break down.

Another potential issue with going into a shorter run in a fasted state is that it increases your stress response. As a result, your body pumps out cortisol and other stress hormones, putting you in a high-alert, fight-or-flight state. That’s not ideal during what’s supposed to be an easy run, and it will result in you feeling like you’re working harder than usual. Afterward, you might be drained because the overall load of the session is higher due to the increased stress on your body.

In contrast, if you eat something before a short run, you’ll have sufficient fuel to provide ready energy, hit your performance target with lower perceived exertion, and keep your stress response under control. Another benefit is that you won’t have dug yourself deeper into a deficit, so it will be easier to fully recover.

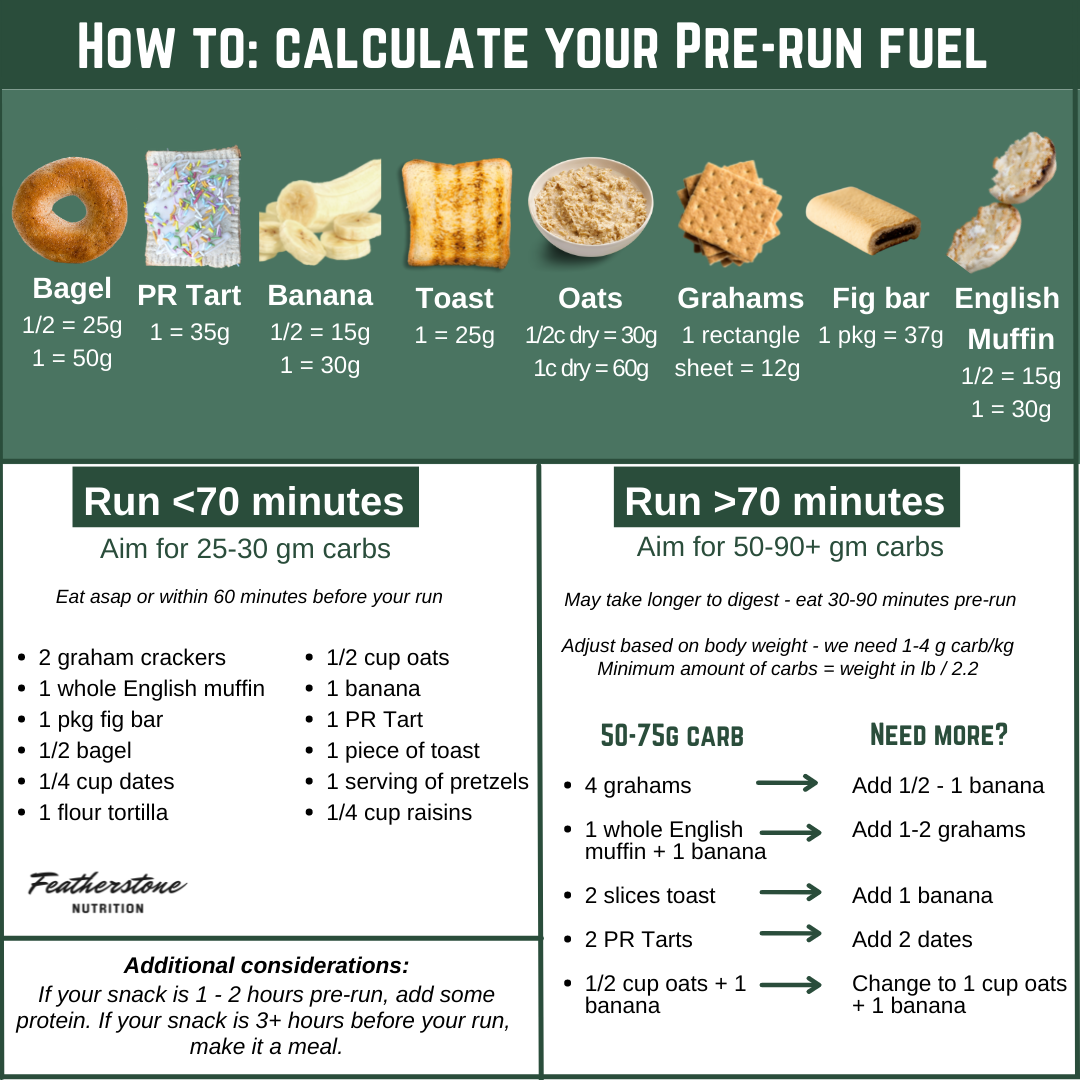

So what should you eat before a short run (70 minutes or less)? The simplest answer is a small amount of simple carbs. For fruit, this could be quarter of a cup of raisins or dates or a banana. Good grain-based options include half a bagel, a piece of toast, an English muffin, or a flour tortilla. Seeking a convenient snack? Then consider a PR Tart, serving of pretzels, or two graham crackers. If you’re looking at nutrition labels, 25 to 30 grams of carbs is the sweet spot, but don’t overthink this. Try eating something from the graphic below in the hour before you start your run, along with 8-16 ounces of fluid so you’re hydrated.

If you’re pushed for time, don’t use this as an excuse to skip fueling. Remember that fast-acting carbs will start to digest in as few as 15 minutes. I get a lot of questions about including fat and protein with pre-training snacks. There’s nothing wrong with this, but as they digest more slowly than simple carbs alone (same goes with fiber), add a bit more time if you’re going to spread butter on your toast, cream cheese on your bagel, or nut butter on your banana. Incorporating protein is a great strategy if you’re snacking one to two hours before a run. If there are three or more hours until you train, you should make your snack a full meal.

What do I need to do differently for long runs?

Longer runs (70 minutes or more) present a different fueling challenge to shorter ones because you’re more likely to burn through the glucose in your bloodstream and at least some of your glycogen stores. So there’s an even greater need to fuel up before you head out. A simple rule of thumb is to double the carb portion that you’re eating before short runs (this can also apply to higher intensity shorter sessions, as these place a greater demand on your body and require it to consume more fuel at a quicker rate.) If you’d snack on two graham crackers for a 45-minute steady state session, try eating four prior to a 90-minute one. You can also start combining carb sources, such as a banana with half a cup of oats, two dates and two PR Tarts, or a fig bar and two pieces of toast (check out more suggestions here).

These quantities should put you into the lower end of the 50-to-90-gram range I typically recommend to clients for longer sessions. You can go a little further by using the equation in the graphic above to determine your carb range, and then consider working with a sports dietitian if you want to really dial in your personalized fueling needs. As you’ll be increasing the amount you’re eating, digestion might take longer so try to eat 30 to 90 minutes before your longer run.

While you shouldn’t need to refuel during shorter runs, you don’t want to completely burn through your carb stores during longer ones and have to rely solely on fat because it’s a slow energy source and not the preferred fuel source. With this in mind, start intra-run fueling within the first 30 to 45 minutes of longer sessions. The range for carb replenishment is anywhere from 40 to 80 grams an hour depending on body size, intensity, training status, and so on, so you’ll need to experiment a little. A good place to start is 1 serving (25-30g carb) every 30 minutes.

Fuel uptake and hydration are interrelated, so I recommend drinking the same 8-16 ounces of fluid as you would before a short run and carrying additional fluids with you for any session lasting an hour or more. If you’re using a hydrogel, you might need less fluid, but if not, try combining your regular gel (or tab, chew, etc.) with water. When it’s hot and/or humid, consider a sports drink that contains electrolytes so you can replace some of the sodium you are losing through sweat.

How should I fuel speed sessions?

A lot of the runners I work with focus on fueling their distance sessions, but speed training also requires smart fueling, whether that’s hill sprints or track intervals. The authors of the ACSM position paper mentioned earlier states that carbohydrate availability enhances long workouts with high intensity intervals while depleted levels of carbs are associated with reduced work rates, impaired skill and concentration, and increased perception of effort.

To avoid such side effects and maximize the benefits of your longer speed workouts (70 to 90 minutes), make sure you’re fueling appropriately. This looks a little different to regularly paced runs of a similar duration. It takes more time for fuel and fluid to empty out of the stomach during high-intensity sessions, with one researcher finding that gastric emptying was around 50 percent slower when VO2 max was at 90 percent. This means you’re at greater risk of nausea, cramping, and other kinds of stomach discomfort if you’re sucking down a mid-workout gel. So eat a carb-rich snack beforehand, only use gels during your warmup so they empty from your stomach before the intensity gets too high, and sip a sports drink in between intervals/reps.

To recap, you need fuel for every kind of run, so no matter if you’re going fast, short, or long, ensure you’re doing some kind of pre-fueling based on simple carbs. Don’t skip or skimp and try experimenting with the guidelines above to find what works for you. Then commit to sticking with it. During longer runs, keep your energy and electrolyte levels up with a combination of gels, water, and sports drinks. Check back soon for part 2 in this series, when we’ll explore fueling for strength training and two-a-days.

Still need help with your fueling and hydration strategy? I’d love to put together a customized plan for you.

1. Louise M Burke et al, “Carbohydrates for Training and Competition,” Journal of Sports Sciences, 2011, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21660838. 2. D Travis Thomas et al, “Nutrition and Athletic Performance,” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, March 2016, available online at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297695609_Nutrition_and_Athletic_Performance. 3. Carl Foster, “Gastric Emptying During Exercise: Influence of Carbohydrate Concentration, Carbohydrate Source, and Exercise Intensity,” Fluid Replacement and Heat Stress, (Washington, D.C., National Academies Press, 1994), available online at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK231135/?report=classic.

Disclaimer: The content in our blog articles provides generalized nutrition guidance. The information above may not apply to everyone. For personalized recommendations, please reach out to your sports dietitian. Individuals who may chose to implement nutrition changes agree that Featherstone Nutrition is not responsible for any injury, damage or loss related to those changes or participation.

[…] yourself a little grace and deliberately build in a bit of flexibility. One way to do this is to get creative with your eating before and after training. Instead of throwing down a couple of graham crackers or pieces of toast before heading out on a […]