5 Things You Can Start Doing Right Now to Improve Your Performance Nutrition

5 Things You Can Start Doing Right Now to Improve Performance Nutrition

Some changes are harder than others. Let’s talk about 5 changes that can upgrade your nutrition starting today. Pick the one that feels the most exciting and achievable and start there!

1. Eat something before every run & cross training session

It’s all too easy to think, “I’m just going for a short run. I don’t need to fuel.” and skip eating beforehand. The problem with doing this is that even though the intensity or duration might not be high, your body still needs energy. If we don’t give our body fuel before a run, we dip into our glycogen stores & cause more stress on our body than needed. This could lead to a dip in speed, early onset fatigue, increased rate of perceived exertion (RPE), and other performance problems, according to a paper published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise.

To get ahead of these, make sure you’re eating at least a little food before you head out to train, with carbs being the basis for your pre-workout snack. Remember: you aren’t just fueling for the work immediately ahead but for the entire week of training. Need more guidance? Check out my recent blog post for in-depth info.

2. Stay hydrated

Even if you fuel before each training session, you’ll also need to stay hydrated before, during, and after to truly support performance. Every process in your body suffers from dehydration, which can lead to cramping, headaches, poor performance, delayed recovery, GI issues, and many other symptoms. You may find it easier to stay hydrated when it’s hot or humid outside because the conditions make you feel more thirsty. But as I shared in a recent article, your thirst can drop by 40 percent in colder weather. So make sure you don’t always drink to thirst and put this hydration plan into action:

- Start your day with 16 oz of fluid like water, coffee, tea, or a sports drink

- Keep a water bottle full of fluid with you throughout the day

- Drink water with meals and snacks

- Take fluid with you on long runs over 70 minutes

- Rehydrate after runs and workouts

3. Include carbs, protein, fat & color at every meal

Beware of any diet that eliminates or limits certain macronutrients or claims that you should be scared of carbs, protein, or fat. Most people find that their bodies work optimally with a balance of all the fuel sources. Carbs are the main source of fuel for the body and brain, protein is vital for muscle building and repair, and fat is necessary for cellular health, combating inflammation, and hormone production.

So try to include all three macronutrients at each mealtime and in your snacks. This should give the right balance of fast-acting and slow-burning fuels to power your best performances, keep your energy level high all day, and feel great. Including a wide range of colors at each meal will mean you’re also incorporating a variety of nutrient-dense fruit and vegetables into your daily diet, which helps ensure you’re getting enough vitamins and minerals.

4. Don't go too long without eating

You’ll be at your best when you’re consuming adequate calories to match your training, recovery, and everyday activity needs from the time you get up until you go to sleep. Sometimes clients don’t have an overall calorie deficit or insufficient macronutrient intake for the total day but still struggle with low energy availability surrounding runs, mood swings, and other physical, cognitive, and emotional issues because they’re digging too deep of an energy deficit around training. If this persists, they’re at risk of developing RED-S (relative energy deficiency in sport), which the International Olympic Committee states can disrupt 12 major body systems.

A simple fix is to surround your training with solid nutrition. And, increase the frequency of your meals and snacks, so your energy intake is distributed evenly throughout the day. Take an honest look at when you’re eating and see if you can find any big gaps. Then plan meals ahead, set reminders to eat, and take snacks with you for those busy times so you don’t go too long without eating. This will help you stay out of large energy deficits, keep your energy levels consistent, and provide enough fuel for whatever comes your way. <<We’re a big fan of shower shakes around here.>>

5. Nail your protein

One of the biggest misconceptions is that runners don’t need extra protein. Endurance activities such as running, swimming, cycling, and triathlon cause muscle damage from repetitive and prolonged movements that require protein to repair. Some studies have shown that endurance athletes underestimate their protein needs by over 20 percent and don’t get enough to kickstart their recovery process after exercise, making it harder to bounce back between sessions. Inadequate protein intake also hampers healing from injury.

Aim to get at least 20 to 40 grams of complete protein (which contains all nine essential amino acids) at each meal, incorporate protein into your snacking strategy, and consume another 20 to 40 grams with some glycogen-replenishing carbs after every training session. You might need even more if you increase your training volume and as you age.

1.D Travis Thomas et al, “Nutrition and Athletic Performance,” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, March 2016, available online at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297695609_Nutrition_and_Athletic_Performance. 2.Margo Mountjoy et al, “International Olympic Committee (IOC) Consensus Statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): 2018 Update,” International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, July 2018, available online at https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/ijsnem/28/4/article-p316.xml.3.3. Harry P. Cintineo et al, “Effects of Protein Supplementation on Performance and Recovery in Resistance and Endurance Training,” Frontiers in Nutrition, September 11, 2018, available online at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6142015/#B28.

Disclaimer: The content in our blog articles provides generalized nutrition guidance. The information above may not apply to everyone. For personalized recommendations, please reach out to your sports dietitian. Individuals who may chose to implement nutrition changes agree that Featherstone Nutrition is not responsible for any injury, damage or loss related to those changes or participation.

Meghann's Favorite Things!

I get asked all the time what products I use for fuel, hydration, and anything else related to nutrition & running. Well, I’m here to make it easy for you! Below are the products that are my favorites – that is not to say that others aren’t awesome, too, as there are soooo many great options out there. If you want to try my favorites, go for it! But, as always, do what works best for you and your fueling needs. All of my favorites are linked on our Recommended Products page, along with many client favorites, too. If you need help figuring out your fueling, reach out for help!

Sports Fuel

I have been a guinea pig for allll the sports fuel. I started many years ago with chews and have tried several gels. Now, my go-to is Maurten 100 and Maurten Caff 100 for marathons, half marathons, or any other road races. For my 70.3, I also took Skratch Super High Carb (FKA Superfuel) on the bike and thought it was a fantastic (and easy) option to get lots of carbs in.

I started many years ago with chews and have tried several gels. Now, my go-to is Maurten 100 and Maurten Caff 100 for marathons, half marathons, or any other road races. For my 70.3, I also took Skratch Super High Carb (FKA Superfuel) on the bike and thought it was a fantastic (and easy) option to get lots of carbs in.

Hydration

It’s no surprise that I’m a huge fan of Skratch products.

Not only do their products provide the electrolytes & some carbs that we need to stay hydrated, but they also taste delicious. Skratch Sports Hydration & Clear Hydration are always on hand at my house. I regularly carry Skratch Sports Hydration in my handheld for all long runs & races. I like Skratch Clear Hydration for some extra daily hydration, and I also added it to my water bottle with Skratch Super High Carb on the bike in my 70.3 for some extra electrolytes. The neat thing about Skratch Clear is it can be concentrated in your bottle to provide more sodium and carbs – without GI upset.

Not only do their products provide the electrolytes & some carbs that we need to stay hydrated, but they also taste delicious. Skratch Sports Hydration & Clear Hydration are always on hand at my house. I regularly carry Skratch Sports Hydration in my handheld for all long runs & races. I like Skratch Clear Hydration for some extra daily hydration, and I also added it to my water bottle with Skratch Super High Carb on the bike in my 70.3 for some extra electrolytes. The neat thing about Skratch Clear is it can be concentrated in your bottle to provide more sodium and carbs – without GI upset.

If you are a heavy or salty sweater <like me!> high

sodium products are a must. Skratch Hyperhydration, Liquid IV and LMNT are all great options to keep you feeling your best during warmer weather. I generally recommend taking Skratch Hyperhydration the night before a race, for those heavy/salty sweaters who need it. Liquid IV is another option for that time, or you can also drink it pre-run or post-run to rehydrate.

sodium products are a must. Skratch Hyperhydration, Liquid IV and LMNT are all great options to keep you feeling your best during warmer weather. I generally recommend taking Skratch Hyperhydration the night before a race, for those heavy/salty sweaters who need it. Liquid IV is another option for that time, or you can also drink it pre-run or post-run to rehydrate.

What good is having the right hydration products  if you don’t have the right handheld to bring along on your run? I have tried tons of different water bottles, and my favorite is the Amphipod 20 oz. handheld. It doesn’t leak and fits nicely in your hand. There is also an option to include a zipper on the sleeve, which is nice for storing gels or hydration products.

if you don’t have the right handheld to bring along on your run? I have tried tons of different water bottles, and my favorite is the Amphipod 20 oz. handheld. It doesn’t leak and fits nicely in your hand. There is also an option to include a zipper on the sleeve, which is nice for storing gels or hydration products.

Last, but not least, my favorite toy to help with  hydration is the hDrop wearable hydration monitor. Wear this guy on a run, and it will tell you your sweat rate, sweat composition, and other stats. My clients and I have found this product extremely helpful to estimate our hydration needs, so we can make sure we are nailing our hydration for our runs & recovery. For more info on hydration, check out my Hydration page.

hydration is the hDrop wearable hydration monitor. Wear this guy on a run, and it will tell you your sweat rate, sweat composition, and other stats. My clients and I have found this product extremely helpful to estimate our hydration needs, so we can make sure we are nailing our hydration for our runs & recovery. For more info on hydration, check out my Hydration page.

Recovery

Speaking of recovery, I have a lot of recipes to nail

recovery on the website, like my favorite EBTB Egg Sandwich but I also like to use Momentous unflavored or vanilla whey protein on busy mornings to get recovery started. My favorite Shower Shake recovery drink is vanilla Momentous whey protein, Skratch Recovery horchata, and almond milk or water.

recovery on the website, like my favorite EBTB Egg Sandwich but I also like to use Momentous unflavored or vanilla whey protein on busy mornings to get recovery started. My favorite Shower Shake recovery drink is vanilla Momentous whey protein, Skratch Recovery horchata, and almond milk or water.

Some more of my favorite recovery products are  Omega 3, Vitamin D, Tart Cherry juice and Vital Proteins collagen. <Read more about recovery here.>

Omega 3, Vitamin D, Tart Cherry juice and Vital Proteins collagen. <Read more about recovery here.>

When my calves are cranky, my GoSleeves really save the day and keep me running. They also make knee, elbow, and ankle sleeves. I wear these calf sleeves on all my easy runs and they have been a game changer in my recovery.

It takes a lot of planning and trial & error to find the products that work best for you. Play around with it! The best products are the ones that you will actually use. If you need figuring out your race day fueling or hydration, please reach out for a consult!

Am I Overfueling?

Am I Overfueling?

We recently explored the warning signs of low energy availability (LEA) and how to bounce back if you’re suffering from relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). Any time I share something about underfueling, I get questions from athletes who are worried they’re going too far the other way. If that sounds like you, let’s dive into the issue and suggest some ways you can best match your nutrition with your energy needs.

How common is overfueling?

Most of the time when my clients aren’t fueling properly, it is due to underfueling, often unintentionally. And as I wrote in our recent RED-S series, it’s often difficult to accurately gauge your energy needs when you’re training hard, meaning that you might actually be underfueling even if you think you’re taking in too many calories. That being said, overfueling still happens – which means we are consuming more energy than our bodies need on a daily basis.

How do I know if I'm overfueling?

If you think you’re consuming too much fuel, there might be some reasons that you believe this. Maybe your body weight or composition isn’t what you want it to be or has recently changed, or maybe you’re struggling to return to what used to be your usual & preferred body composition. Remember there are other factors that impact our weight, like chronic stress, sleep deprivation, hormonal changes, chronically not eating enough, or not eating balanced meals, amongst other factors.

At times there may be a mismatch between the energy you need and what you’re eating on a daily basis. If you are consuming more than your body needs for daily functioning, exercise & recovery, you might be overfueling. It can be hard to know if we are truly overfueling or not. We may be overfueling if we feel overly full after meals and snacks, excessively snack when we’re not hungry, eating to cope with feelings or other emotions, or over-restricting during the day and eating more than our body needs at night.

Am I taking too many gels on long runs?

As I’ve written about before, I see more athletes underfueling during runs, rides, swims, and lifting sessions than those who are on the other end of the spectrum. But I have seen a couple of athletes taking in more fuel than their body needed and experiencing negative consequences. This could be because you’ve had a bonking experience in the past, are anxious about getting in enough fuel, or have heard all the new research about fueling more and giving it a whirl without practicing it in training.

While fueling needs vary, I typically recommend getting your first gel down within 30 minutes and then consuming another every half hour. If you’re an elite competitor or a larger athlete, you might need more fuel than this, but taking too many gels may cause performance tanking issues like nausea, vomiting, stomach cramping, and discomfort. If you need help calculating your gel intake, take a look at my free online calculator, Customized Race Day Fuel & Hydration plan or reach out for a consultation.

Am I eating too much after training?

One of the most common mistakes I see runners and other athletes making is focusing too much on the number of calories they’re burning during training. And focusing on ‘eating back’ all the calories ‘burned’ during a run.

One thing I see athletes do is have a “free for all” mentality on long run/workout days – thinking because they burned x amount of calories, they can eat whatever they want for the rest of the day. However, doing so can make you overshoot your fueling needs, leading to excess calorie intake. I’d rather see my runners focus on spreading out that energy intake pre-run and post-run so that they meet the demands of training and kickstart recovery afterward. Check out my piece on recovery nutrition for runners to see more detailed tips.

Balancing meals & snacks

Another way that athletes sometimes end up consuming more energy than they need is by grazing throughout the day instead of eating solid meals. Working from home, changes in appetite and busy schedules make grazing very easy. But if you’re constantly snacking, it’s easy to eat more than you need – energy-wise – yet miss the boat on the balance nutrition we get with a planned meal. One way to remedy this is to eat meals that are more filling and better balanced. These should typically contain plenty of protein and carbs. Don’t forget to include some fat, as this is the most calorie-dense macronutrient and will help you stay full for longer. Fiber is another nutrient that will help to keep you satiated between meals. You should feel like you’ve had enough after eating, without being uncomfortable. The same goes for snacks.

Tips to avoid overfueling:

-

Eat 3 meals per day – balanced with carbs, protein, fat and color. Make sure you are eating enough protein at meals.

-

Include fiber in your meals <except for pre-run meals> to help with satiety.

-

Make sure you nail your recovery meal post-run/workout.

-

Include snacks if your timing between meals is greater than 4 hours or if you are hungry in between meals.

-

Stay hydrated.

-

Reach out to a sports dietitian to evaluate your intake for your current training & help you gain confidence in your fueling plan.

-

Looking to create new habits to improve your nutrition & body composition? The Off-Season Body Composition Program may be the perfect option for you.

Disclaimer: The content in our blog articles provides generalized nutrition guidance. The information above may not apply to everyone. For personalized recommendations, please reach out to your sports dietitian. Individuals who may chose to implement nutrition changes agree that Featherstone Nutrition is not responsible for any injury, damage or loss related to those changes or participation.

The Graham Slam!

It’s no secret that I am a HUGE fan of graham crackers for pre-run fuel. Some have dubbed me as the Graham Queen, and I will happily take that title. Day in & day out, that’s my choice. I wake up most days at 4am, drink my coffee & eat my grahams, then I’m out the door for an early morning run. I have always preferred Honey Maid grahams, but you all were wondering what the best graham out there was. So, I set out on a quest to find the BEST grahams. What could be a better way to do that than to have a blind taste test with grahams aka The Graham Slam!

I ordered 10 different types of grahams, some I had tried, and some that I had not. I ordered several blindfolds from Amazon <ok, maybe far too many, but they were hilarious!> I was shooed off to another room, while my trusty sidekick numbered the bottom of each box & got the the grahams all ready.

One by one, I tasted the grahams. There were several that I enjoyed and would gladly eat again. Some were so-so and lacked flavor. Lastly, there were a couple that I would not choose to ever taste again. Watch this Reel below to see the Graham Slam in action.

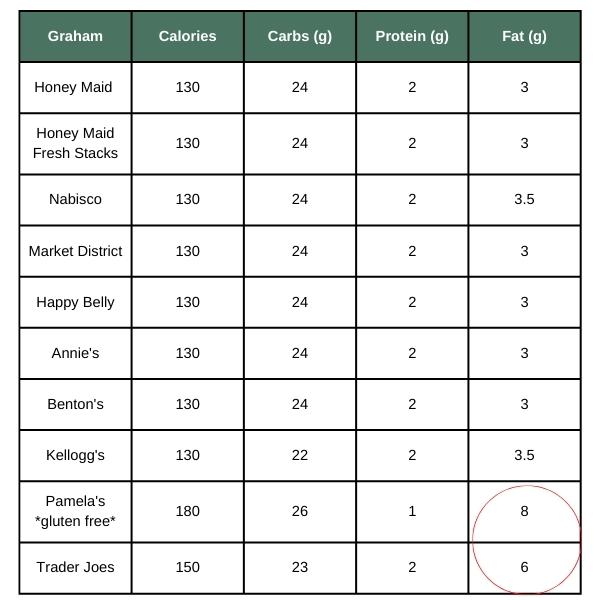

I excluded Pamela’s & Trader Joe’s from my list because those aren’t “true” grahams to me. The texture of Pamela’s wasn’t very graham-like, and Trader Joe’s was more like a cookie <although, pretty tasty>. Here’s my list in order of preference from the blind taste test, starting with my least favorite:

8. Kellogg’s – didn’t taste like anything

7. Benton’s (Aldi) – love Aldi, don’t love their grahams

6. Annie’s – didn’t care for the flavor

5. Happy Belly (Amazon) – ok but bland

4. Market District (Target) – pretty good, would buy these again

3. Nabisco – tasty! I would eat these as a backup.

2. Honey Maid Fresh Stacks – a little different than the regular kind but very good

1. Honey Maid – my favorite is indeed my favorite, even while blindfolded!

Next, we wanted to see if I REALLY knew my favorite grahams from the competitors. We did a few side-by-side, blindfolded taste tests. <See the video below> I was a little thrown by the last one <wait for it>, but at the end of the day, I know my Honey Maids!

Most grahams out there, including the grahams I tested, have a very similar macronutrient composition. However, it’s important to note that two of these grahams stood out. The first being Trader Joe’s – they were more like a cookie, and I am not surprised to see some added fat in there. Second, the gluten-free Pamela’s. One-serving of these may sit just fine, but if you double them up as pre-run fuel for a long run, that fat content might cause some GI distress. Definitely something to consider!

Winner, Winner!

Honey Maid Grahams

We want to know! What do you want Meghann to blind taste test next?

RED-S: Long-Term Consequences & Recovery

RED-S: Long-Term Consequences & Recovery

In the previous part of this series, we looked at what low energy availability (LEA) is, how it might eventually lead to relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S), and the short-term symptoms. Now it’s time to talk about some of the long-term consequences and how you can bounce back.

Can RED-S lead to injuries?

Dealing with acute, short-term LEA can be frustrating enough, but if it continues for longer periods of time, you might start to notice more serious health issues developing and bigger drop-offs in your training and recovery. As with inadequate vitamin D and calcium intake, chronic LEA increases the risk of low bone mineral density and decreased bone strength, contributing to a higher incidence of stress fractures. If you’re already dealing with a bone injury, consuming inadequate calories and lack of solid nutrition can slow your healing process. RED-S might also elevate your chances of developing other overuse injuries.

RED-S & menstrual cycle changes

In last week’s post, I shared that 30 kcal per kilogram of fat-free mass (FFM) or less was considered to be the danger zone for LEA. While this is a good clinical rule of thumb, some studies have shown that women who were above this threshold still had menstrual functions that were all over the map. Researchers from Penn State found that multiple kinds of disturbances – including luteal phase defect, anovulation, oligomenorrhea – can become more frequent when female athletes have persistent energy deficits.

What are other consequences of RED-S?

According to the International Olympic Committee, RED-S doesn’t merely compromise bone health and disturb the menstrual cycle. Persistent LEA can also cause a whole host of health issues and exacerbate existing ones in many other body systems. Some of the long-term effects include:

Endocrine

- Disrupted levels of estrogen and progesterone in women

- Low testosterone in men

Metabolic

- A 2015 study on the female athlete triad (the interrelationship between LEA, menstrual function, and bone mineral density) found 53 percent of LEA participants had a decreased resting metabolic rate (RMR). Others were struggling with low bone density, high cholesterol, and low blood sugar

- Impaired ability to use glucose effectively and sometimes low blood glucose levels

Hematological

- Low ferritin and iron deficiency anemia

- Iron deficiency can further decrease appetite

Cardiovascular

- Higher lipids

- Cardiac abnormalities like lower or higher heart rate

Gastrointestinal

- Delayed or faster gastric emptying

- Diarrhea and constipation

Immunological

- Increased risk of illness

- Decreased immunity

Psychological

- Depression and anxiety

- Mood disturbances

Growth and Development

- Stunted growth in adolescents

- Decreased growth hormone release

What nutrition changes can I make to increase energy intake?

When someone finds out they have RED-S, the logical conclusion is that they simply need to eat more. This can certainly be the case, as having an overall calorie deficit is a major part of the problem. However, a bit more nuance is usually needed to remedy the issue, which is where a dietitian can help. When I look at a client’s eating habits across an entire day, I often see that there are certain times when they aren’t taking in enough energy, leading to lopsided energy intake over a 24-hour period and an overall deficit.

For example, perhaps your mornings are crazy because of your commute or school drop-off, so you often skip breakfast. Or maybe work gets so busy that you don’t eat lunch several days a week. So by the time you get to midafternoon, you’re already energy deficient. Then you go and run hard, digging an even deeper hole. Once you’ve had help to pinpoint specific fueling gaps, you can start to fill these so that you have enough energy for daily life and training.

What are some other ways that a sports dietitian can help with RED-S?

A qualified professional can confirm whether or not you have RED-S or are struggling with LEA, and then create a comprehensive plan to help you bounce back. In addition to identifying gaps in your eating schedule, they can suggest better choices for snacks and meals, recommend supplements if needed, and take into account the big picture of your training, recovery, and lifestyle to help you find a more sustainable energy balance. As I wrote in a previous post, it’s time to stop being scared of carbs and embrace a well-balanced approach to nutrition.

Sometimes the solutions to low energy availability are simple ones, such as incorporating more calorie-dense foods. For example, you could start adding a couple of spoonfuls of nut or seed butter to your post-workout shower shake. Frequency is another easy variable to change, as adding morning and afternoon snacks will increase your energy intake. Some of my clients have also benefited from eating a pre-bedtime snack, like a Greek yogurt parfait with berries & granola. Others have started eating a second breakfast. Ultimately, you have to fuel like you hope to perform, live, and recover.

How do I start increasing energy availability?

Most people’s eating is primarily directed by their appetite, but remember that this is often a lagging indicator of needing energy and can be disrupted by your sleep pattern, exercise, caffeine, and other factors. You’ll be better off planning for your fueling needs like you would build out your training sessions. A good rule of thumb is to fit in at least three meals and two snacks each day, not going more than 3 hours without eating and focusing on balancing adequate carbs, protein & fat. While it’s important to get enough carbs and protein, they only contain four calories per gram, whereas fat has nine, making it an easy way to up your energy intake.

Also make sure you surround your energy expenditure – whether that’s a formalized session like a run or gym workout, or family activities – with more nutrition. In other words, eat before, during (when needed), and after exercise, and recognize that more intensity and volume will increase your fueling needs, such as if you start strength training or doing some two-a-days. It’s easy to get discouraged if you have RED-S/LEA but know that you have the power to overcome this and that there are people out there with the passion and knowledge to help you recover. Some of my clients have reported starting to feel and perform better in a few days once they increase their energy availability.

If after trying these tips you still can’t keep up with your energy needs, then try cutting back on your training temporarily. Then when your schedule and lifestyle allow, scale up your workouts and nutrition again simultaneously.

If you’re struggling with LEA or RED-S and need help, please reach out. I’ve helped many clients to overcome this issue and would welcome the chance to get you back on the path to optimal performance and health.

1.Nancy I Williams et al, “Magnitude of Daily Energy Deficit Predicts Frequency but not Severity of Menstrual Disturbances Associated with Exercise and Caloric Restriction,” American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology, and Metabolism, January 2015, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25352438. 2.Margo Mountjoy et al, “International Olympic Committee (IOC) Consensus Statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): 2018 Update,” International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, July 2018, available online at https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/ijsnem/28/4/article-p316.xml.3.A Melin et al, “Energy Availability and the Female Athlete Triad in Elite Endurance Athletes,” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, October 2015, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24888644.

Disclaimer: The content in our blog articles provides generalized nutrition guidance. The information above may not apply to everyone. For personalized recommendations, please reach out to your sports dietitian. Individuals who may chose to implement nutrition changes agree that Featherstone Nutrition is not responsible for any injury, damage or loss related to those changes or participation.

RED-S: Are you at risk?

RED-S: Are you at risk?

We all have days when our schedules get the better of us and we end up missing meals or not getting enough to eat overall. But if underfueling becomes the norm (intentionally or unintentionally), you might be at risk of developing Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). Let’s look at how this happens, what the warning signs are, and how an energy deficit can impact your performance, recovery and health.

Low Energy Availability (LEA) & RED-S

Finding yourself in a calorie deficit occasionally probably isn’t going to be a problem, if you recognize it and make changes. But when you consistently have insufficient energy intake or the amount of energy you are expending is far greater than your intake, or both you might have low energy availability (LEA) which could lead to RED-S. According to a consensus statement by the International Olympic Committee, “LEA, which underpins the concept of RED-S, is a mismatch between an athlete’s energy intake (diet) and the energy expended in exercise, leaving inadequate energy to support the functions required by the body to maintain optimal health and performance.”

As a result of this mismatch between how much energy your body needs and how much you’re giving it, you can begin experiencing health issues, a performance drop-off, and inadequate recovery, as your body struggles to find ways to get the energy it needs for basic functions while also fueling your training and recovery. The IOC paper defined RED-S as “impaired physiological functioning caused by relative energy deficiency, and includes but is not limited to impairments of metabolic rate, menstrual function, bone health, immunity, protein synthesis, and cardiovascular health.”

What is energy availability?

One of the ways that registered dietitians and other practitioners try to identify whether someone is suffering from RED-S or a similar condition is by calculating their energy availability. Calculating food energy intake minus exercise energy expenditure equals energy availability. The leftover ‘energy availability’ must be enough energy for your body to fuel basic physiological processes.

For many athletes, they need to be consuming 45 kcal/kg FFM (fat-free mass) at baseline + recouping any energy needed for training. An energy availability of 30 kcal/kg FFM or below, is called ‘low energy availability.’ This means the amount of calories you’re consuming cannot support your daily energy needs plus the fuel your body requires during and after exercise. The deficit compromises body systems that need fuel, which start to shut down to preserve energy and keep you alive.

Calculating your exact FFM is difficult and not accessible to most people. FFM is measured or estimated by dietitians or medical professionals – so if you are concerned in this area, please reach out to your sports dietitian or physician.

Are athletes more susceptible to RED-S?

There’s a reason that the S in RED-S stands for sport. Whether you’re a runner, cyclist, triathlete, or dabble in multiple disciplines, the more active you are, the greater number of calories you’ll burn. It isn’t just about your energy needs during training either. Your body needs extra fuel to support recovery and lean muscle mass is more metabolically demanding. Plus, there are many energy-dependent processes your body and brain need to perform to keep you functioning. Overlooking these factors is why some athletes drastically underestimate their fueling needs and can slip into chronic energy deficiency. Studies on runners suggest LEA (low energy availability) is most prevalent with high training loads, high energy expenditure, and low energy intake. A sudden increase in mileage and/or intensity, changing nutrition choices or restricting new foods, lack of hunger cues or decreased appetite with higher training loads, and competing in more races could all put an athlete at greater risk for RED-S if they are not conscious of proper fueling.

Why are female athletes more at risk for developing RED-S?

While chronic energy deficiency is more prevalent among women, male athletes can suffer from RED-S (see recent Ryan Hall post). Reasons can include societal pressure to look a certain way as a runner or endurance athlete, advice from a coach that leaner improves race times, lower caloric intake to begin with, disordered eating, lack of knowledge on how to fuel your body for your training load, and an energy deficit from pursuing a new dietary pattern and restricting foods or times of nutrition.

RED-S & Eating Disorders

It’s a misconception that only people who are battling eating disorders struggle with RED-S. RED-S isn’t always paired with disordered eating, fear of consuming too many calories, or other unhealthy perspectives toward food. One of the most common causes I see among my clients is unintentional underfueling – that they simply underestimate the amount of fuel they need to power their performance and recovery, while also meeting their daily energy needs.

Why can it be hard to spot RED-S?

Sometimes, RED-S presents several warning signs that pop up like an engine light in your car. However, researchers from the University of North Carolina found that when observing male athletes with RED-S, “participants displayed no major hormonal or bone health disturbances” in the short term. This means that it could be harder to pinpoint the condition in men than in women, who often start to experience changes in their period and/or stress fractures (more on the long-term effects of RED-S to come in part two). That being said, an article by Brown University stated that “This often unrecognized disorder can include low energy availability (inadequate caloric intake); with or without disordered eating; amenorrhea (lack of menstrual periods); and low bone mineral density.” In other words, RED-S can go undiagnosed in women too.

What are the short-term symptoms of RED-S?

When red flags do appear, they typically impact performance and recovery first, and then begin to extend into overall physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing. Common symptoms of RED-S include:

- Poor performance (such as inability to hit or hold paces, quicker time to exhaustion, and increased perceived effort)

- Delayed recovery

- Decreased power and strength output

- Chronic fatigue

- Feeling heavy, lethargic, and low on energy

- Loss of bodyweight and muscle mass

- Sleep disturbances

- Nagging injuries

- Disrupted menstrual cycle and/or missed period

- Emotional volatility and irritability

- Change in appetite

- Delayed recovery

- Lower heart rate variability (HRV)

Check back soon for part two in this series, when we’ll explore what you can do to reverse RED-S (hint: it might be easier than you think, and you CAN come back from this!).

1.Margo Mountjoy et al, “International Olympic Committee (IOC) Consensus Statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): 2018 Update,” International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, July 2018, available online at https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/ijsnem/28/4/article-p316.xml. 2.Amy R Lane et al, “Energy Availability and RED-S Risk Factors in Competitive, Non-elite Male Endurance Athletes,” Translational Medicine and Exercise Prescription, June 2021, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34296227. 3. “Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S),” Brown University, available online at https://www.brown.edu/campus-life/health/services/promotion/nutrition-eating-concerns-sports-nutrition/relative-energy-deficiency-sport-red-s.

Disclaimer: The content in our blog articles provides generalized nutrition guidance. The information above may not apply to everyone. For personalized recommendations, please reach out to your sports dietitian. Individuals who may chose to implement nutrition changes agree that Featherstone Nutrition is not responsible for any injury, damage or loss related to those changes or participation.

Am I Getting Enough Vitamin D?

Am I Getting Enough Vitamin D?

In our most recent series, we explored why you might be low in iron, how to tell, and what to do about it. Now let’s look at another vital micronutrient: vitamin D. Like iron, it’s essential for performance and health, and yet many people are chronically deficient. Keep reading to learn which functions vitamin D performs, what happens when your levels dip, and how to get them back up again.

What does Vitamin D do for me?

Vitamin D helps us absorb calcium and phosphate from our intestines and then helps to regulate their storage & blood concentrations throughout our body, making it essential for the formation of new bone and the preservation of existing skeletal mass. Without enough Vitamin D, our bones can become brittle. Vitamin D is also involved in both innate and adaptive immunity, according to a team of British and Canadian researchers. It’s also involved in cardiovascular health and has a neuroprotective effect on the brain.

Why are so many of us Vitamin D deficient & how common is it?

It’s arguable that vitamin D is the most prevalent micronutrient deficiency. While many other vitamins and minerals can be consumed through a well-rounded diet, vitamin D’s production is mainly prompted by exposure to direct sunlight, and specifically UVB rays. We’ll look at some food sources in a moment, but Vitamin D is not prevalent in the foods we eat most often. Combine that with the fact that American adults spend the majority of their time indoors, and it’s little wonder that up to 90 percent of the population is vitamin D deficient, per a paper published in Frontiers in Physiology.

I mostly train outside. Won't I get enough Vitamin D?

One would assume yes, but the research on vitamin D shows that even people who are active in sunny, warm climates have a high rate of deficiency. This is particularly prevalent in the Northern Hemisphere during winter, as the weak sun, cloudy weather, and early sunset conspire to keep us from synthesizing enough vitamin D. Plus, if you’re training in cold wintry conditions, you’re most likely layering up and covering parts of your body – like your hands and head – that are open to the sun at other times of year. Or, if you’re always running before the sun comes up, no Vitamin D production there. So just running outdoors might not be cutting it from a vitamin D standpoint.

How do I know if my Vitamin D is too low? What should my level be?

Vitamin D deficiency often has no symptoms at all. Symptoms may include fatigue, bone pain, muscle weakness, or mood changes. As some of these can be linked to other issues and multi-factorial, I often encourage my athletes to get a blood panel that includes serum vitamin D. I typically recommend that my athletes target 40 ng/mL or more. Anecdotally, around 75 percent of my athletes tested who are not supplementing have low Vitamin D.

How can low Vitamin D impact my health & performance?

Insufficient vitamin D puts you at greater risk of getting sick and could prolong certain symptoms, which is not helpful from a performance standpoint. If you have a bone injury, it may take longer to heal if you have insufficient levels of Vitamin D. But perhaps the most concerning side effect of low vitamin D is the elevated incidence of stress fractures.

A study of 802 NCAA Division 1 male and female athletes discovered that they increased their risk of stress fracture by 12% when their serum vitamin D was lower than 20 ng/mL and/or they didn’t take a vitamin D supplement, when compared to those whose serum vitamin D levels were >40 ng/mL and athletes with low vitamin D who were supplementing. The authors wrote that “Low vitamin D levels along with high-intensity athletic training may put an athlete at increased risk for a stress fracture.”

What can I do to increase my Vitamin D level?

If you know or suspect that you’re lacking in vitamin D, researchers from the University of Wyoming suggest a three-part strategy. First, try to get outside in direct sunlight for 5-30 minutes between 10 am and 3 pm as often as possible, as this is the easiest way to stimulate your body’s production. Skip the sunscreen for this short duration and try to get your sun session at least twice a week. (Note: We are not suggesting to skip your sunscreen altogether – as little as 5 minutes per day can help improve Vitamin D levels. If you are at high risk for skin cancer or have other skin conditions, this may not be an option for you, please consult your physician.) You can also try to eat more salmon, mackerel, tuna, and other oily fish, along with plenty of eggs (don’t toss the yolks!). As a bonus, these all provide inflammation-fighting omega-3 fatty acids. Animal foods like these contain D3, the most readily absorbed form, as do some fortified products like milk and cereal. Plant-based sources include leafy green vegetables, sesame seeds, and mushrooms, but these are in the D2 form, which has less bioavailability.

Even the richest food sources are unlikely to supply the consistent amount of vitamin D you need, which is where a third tactic becomes useful: supplementation. 1,000 to 2,000 IUs of vitamin D3 per day is a solid starting point. Your doctor or dietitian might recommend more, depending on your situation. The NCAA researchers noted that if you’re low in vitamin D, supplementation helps elevate serum levels and reduces the risk of stress fracture.

1. Emma L Bishop et al, “Vitamin D and Immune Regulation: Antibacterial, Antiviral, Anti-Inflammatory,” JBMR Plus, September 2020, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32904944. 2.Igor Bendik et al, “Vitamin D: A Critical and Essential Micronutrient for Human Health,” Frontiers in Physiology, July 2014, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25071593. 3.David Millward et al, “Association of Serum Vitamin D Levels and Stress Fractures in Collegiate Athletes,” Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, December 2020, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33816638. 4.Kentz S Willis et al, “Should We Be Concerned About the Vitamin D Status of Athletes?” International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, April 2008, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18458363.

Disclaimer: The content in our blog articles provides generalized nutrition guidance. The information above may not apply to everyone. For personalized recommendations, please reach out to your sports dietitian. Individuals who may chose to implement nutrition changes agree that Featherstone Nutrition is not responsible for any injury, damage or loss related to those changes or participation.

Hydration Tips for Winter

Hydration Tips for Winter

Wherever you are in your running journey right now, it’s important that you’re hydrating adequately. For those who live in a climate with chilly winter months, hydration this time of year isn’t top of mind for most people. But, if you’re going to get the gains you want and recover well, it’s essential. Let’s roll through some best practices for keeping your hydration on point while it’s chilly outside.

Why is it hard to stay hydrated in the winter?

When you’re working out in hot and/or humid weather, getting enough fluids and replenishing your electrolytes can be tricky because of the conditions and the amount you’re sweating. But at least the need to hydrate is pretty obvious because of what you feel and observe about your body, and to keep you alive, your body’s thirst mechanism is finely attuned when it’s warm. But when the mercury plunges, you probably don’t feel hot and clammy and can’t see the sweat on your skin, so you’re without the usual cues that prompt you to drink.

A team of researchers from the University of New Hampshire found that during moderate exercise (at around 50 percent of VO2 max) and at rest in the cold, participants’ thirst sensation dropped off by up to 40 percent, which they speculated might be because of peripheral blood vessels constricting. In other words, drink to thirst tactics that serve you well for the rest of the year aren’t as effective during winter.

Do I need to drink less in cold weather?

At first glance, it might be tempting to look at the winter thirst study and think that maybe the people involved were just using way less water. But in fact, the typical recommendations for around three liters of fluid intake per day that the National Academies of Sciences outlined (while noting that this is merely the median in their data and that individuals’ needs vary based on activity level, bodyweight, and other factors) hold true all year long. Sure, you might not be sweating as much as at the peak of summer, but exercise still drains your fluid reservoir and you need enough water to also preserve the function of your nervous, cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, and other systems during daily life.

How do I know how my fluid needs change in cold weather?

For many athletes, it should be enough to know that although you don’t feel or see sweat as obviously when it’s cold, you’re still sweating and internally, your body is using fluid just like it does in warmer weather. But maybe you like to quantify your physiology and training and want to explore your own seasonal hydration variations. In which case, you could use a simple sweat rate calculator like the one on my website to dig a little deeper. Or if you have a continuous hydration monitoring device such as an hDrop, you could use this during your runs, rides, and gym workouts to objectively measure your sweat rate and composition.

Also take into account that the amount you sweat and how many electrolytes you lose can be altered by many factors, per a paper published in Sports Medicine. Whether you’re training outside on roads, trails, or a track or inside on a treadmill will likely make a difference, as will your layering strategy when you’re outdoors, the volume and intensity of your training, and other factors. The key is to experiment with all these variables and then dial in your fluid intake accordingly to ensure you’re getting enough fluid.

If I don't want to measure sweat rate, how much should I drink?

You might not want to take it as far as quantifying your winter hydration needs. In which case, following a few generic rules of thumb may be sufficient. Here are some best practices I suggest to my clients:

- Start your day with 16 oz of fluid like water, coffee, tea, or a sports drink (or a combination of these)

- Keep a water bottle full of fluid with you throughout the day

- Drink water with meals and snacks

- Take fluid with you on runs lasting over 1 hour

- Rehydrate after runs and workouts

Remember that these are merely guidelines and be sure to adjust them based on what’s working well and what needs to be tweaked. You’ll know you’re not getting enough fluids if your performance drops off, you struggle to bounce back between sessions, or you start feeling off in general. In addition to drinking plenty of water and using your usual sports drinks before, during, and after longer lifting and endurance sessions, you can also top up your fluid levels through your diet. Most fruit and vegetables have a high water content, making them the perfect complement to your winter hydration strategy.

1.Robert W Kenefick et al, “Thirst Sensations and AVP Responses at Rest and During Exercise-Cold Exposure,” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, September 2004, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15354034. 2.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2015), available online at https://doi.org/10.17226/10925.https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/10925/chapter/6#145. 3.Lindsay B Baker, “Sweating Rate and Sweat Sodium Concentration in Athletes: A Review of Methodology and Intra/Interindividual Variability,” Sports Medicine, March 2017, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28332116.

Disclaimer: The content in our blog articles provides generalized nutrition guidance. The information above may not apply to everyone. For personalized recommendations, please reach out to your sports dietitian. Individuals who may chose to implement nutrition changes agree that Featherstone Nutrition is not responsible for any injury, damage or loss related to those changes or participation.

1-on-1 vs. Group Nutrition Coaching

1-on-1 vs. Group Nutrition Coaching: Which One is Right for Me?

In the previous two parts of this series, we shared how to enjoy holiday foods to the fullest and why the off-season is the best time to focus on your body composition goals. While we hope these articles and other content is helpful, sometimes you might want to dive deeper into optimizing nutrition to improve your performance, health, or both. In which case, expert coaching from a sports dietitian would be the way to go. Let’s take a look at the differences between 1-on-1 and group nutrition coaching.

How can I benefit from nutrition coaching?

A lot of clients come to me when they’ve decided to commit to training and racing and have big goals. This could be a new thing for them, and they might not know how to fuel the increase in mileage and intensity that a new program demands. Or, perhaps a more seasoned athlete who has been competitive for several years could be working with a running, cycling, or triathlon coach, have dialed in other areas of performance, but never focused on nutrition. Another reason why people reach out is that they’re struggling with a serious acute or chronic injury and think that eating better could help, but don’t know how. Or maybe they are stuck on a plateau or have seen their training paces and finish times stall.

What do my clients like best about 1-on-1 nutrition coaching?

1-on-1 coaching is great for anyone looking to improve their nutrition and is also looking for accountability and a personalized approach. One of the advantages is that you’ll receive more dedicated and personalized attention from me on an ongoing basis. We’ll also be able to take a comprehensive view of your previous training, racing, and injury history and see exactly where you’re at currently with your eating and supplementation. Then we can map out a plan for how to move forward to reach your goals. This is a good option if you do better in 1-on-1 conversations, rather than in a group setting, have a complex medical history, or feel like you need more accountability.

Depending on the package you choose, we’ll have weekly calls or email check-ins. These will be very personalized to your needs, lifestyle, and goals. We can focus on performance nutrition, hydration, body composition, food allergies, or whatever you need. Over time, we can change directions or explore other areas as needed. I believe in creating lasting relationships that continue to deliver long-term value and welcome the chance to team up.

If you’re interested in a personalized, 1-on-1 plan, the first step is to complete an application to get on the waitlist. Then as soon as possible, our team will contact you to get going once a spot opens up.

When is group coaching the right fit?

Clients often come into one of my nutrition coaching groups seeking the education and community that a team environment provides. It’s an opportunity to not only learn about and apply sound nutritional principles to training, racing, and life, but also to develop new friendships and a lasting support system. Athletes who’ve typically trained alone often come alive in this group setting, as they welcome being part of a tight-knit community of runners who are pursuing similar performance goals. This option might be best if you need more encouragement, like to hear other people’s suggestions and experiences while sharing your own, and respond well in a class environment.

My group program features weekly live classes taught by me, which are also recorded in case you have a scheduling conflict or want to re-watch a session later on-demand. Each class topic focuses on an aspect of performance nutrition and hydration that will prepare you to train for and race in half and full marathons. In addition to class sessions, there are weekly slides, tools, and homework to supplement the course content. We offer support via a private Slack channel and there’s an opportunity to be as much or as little involved as you like and your lifestyle allows.

We have new race and distance-specific groups opening up now for 2023. Fueled for Boston is for anyone running Boston 2023, and we’re also offering spring half or full marathon coaching that’s best for races after April 11, 2023. Click here to learn more and sign up today!

No matter what level of nutrition coaching you are looking for, we have something for you! Not interested in coaching just yet but want some help gearing up for a specific race? Take a look at our Customized Nutrition Plans or apply for a one-time consultation. And make sure you are taking advantage of our free resources: Instagram, carb loading, hydration, race day fueling & recovery.

Disclaimer: The content in our blog articles provides generalized nutrition guidance. The information above may not apply to everyone. For personalized recommendations, please reach out to your sports dietitian. Individuals who may chose to implement nutrition changes agree that Featherstone Nutrition is not responsible for any injury, damage or loss related to those changes or participation.

Focusing on Nutrition & Body Composition in the Off-Season

Focusing on Nutrition & Body Composition in the Off-Season

During the racing season, most of your goals are probably performance focused, whether that’s finishing your first marathon, setting a PR, or stepping up to a new distance successfully. So you try to use your nutrition to support the pursuit of these targets, like fueling right on race day. But with spring events still to come and the holidays behind us, maybe you’ve got different aims in mind now. I’ve recently had a lot of people reach out asking for help with body composition changes they want to make during the off-season, which is what this post is all about.

Why is the off-season a good time to focus on nutrition for body composition?

Unless you’re gearing up for an early 2023 race, you might have eight to 12 weeks (or more) of downtime, which provides you with the perfect opportunity to dial in your nutrition. During racing season, it’s difficult to do much around body composition because you’re fueling for performance in training and competition. But now that there’s less mileage, intensity, and frequency for a while, you’ve got more bandwidth to focus on other elements of your overall well-being.

What’s the best way to approach nutrition for body composition?

The key is concentrating on healthy eating. This isn’t the same as dieting, which implies restricting or eliminating certain foods and attaching unhelpful “good” or “bad” labels. When people diet, it puts the focus on the scale and eliminating certain foods or food groups. In many cases, it is extremely harmful and can start to create compulsive behaviors and obsessions, not to mention, these restrictive diets are not sustainable. You’ll be better off setting a goal that isn’t weight-centric, such as increasing lean muscle mass, getting stronger, or feeling better in certain clothes.

How can I evaluate my eating habits?

A good starting point when you’re targeting body composition changes is to evaluate your current meal and snack patterns. Which areas are you nailing, like sticking to consistent eating times? And is there something you could get better at, such as including protein with every meal? Once you’ve assessed what you’re doing currently, you’ll have a better understanding of what needs to change, what you can keep the same, and what you can double down on.

Should I track my nutrition or not?

Some of my clients have an intuitive feel for what they’re eating and when, while others struggle to get a handle on what their eating patterns look like from day to day. If you fall in this second category, you might find it helpful to see where you’re at and what you could tweak. Don’t get fixated on every single detail, start weighing your food, or count calories, but rather stick to the basics of recording meals & snacks, timing and monitoring feelings of hunger, satiety, and boredom related to your food. If you’ve struggled with disordered eating or anxiety, tracking probably isn’t the best approach for you.

Which changes can I start making now?

It might seem counterintuitive, but big body composition wins can come from just a few small changes. For example, if you often skip breakfast because your morning is hectic or fitting in lunch around your work schedule is tricky, you might overeat later to try to compensate. In which case, getting intentional around eating those essential meals every day is an easy fix. The off-season can also be a good time to get back to eating things you’ve missed, like big salads or extra veggies. You might have more time to cook and bake if you’re training less, which could allow you to make some new snacks like pumpkin spice and mint chocolate energy bites and gingerbread blender muffins that will keep your energy level high between meals and power you through your off-season workouts. If you find that you’re not getting the right balance of carbs, protein, and fat, you could start trying to include all three in each meal.

How can I get help with my body composition goals?

Recently, I’ve had a lot of people writing to me via Instagram and the Fuel for the Sole podcast asking questions about their nutrition at this time of year. This led me to create a new Off-Season Body Composition Series. It features four virtual classes that you can watch and replay at your convenience. Then you’ll get homework that will guide you on what to evaluate and focus on before the next class.

We’ll cover how to evaluate body composition, take genetics into account, and set goals in week one. Then in week two, we’ll review macronutrients and look at how to better balance meals and snacks. Moving into week three, you’ll learn how to spot behaviors you can change and when to create new ones that support your healthiest body comp. Finally in week four, you’ll discover the reasons that your weight might fluctuate, which goals it’s better to focus on instead, and how to chase them effectively.

This is NOT a weight loss course or crash diet. It’s a way to empower yourself to self-identify your strengths, find controllable factors you can improve, and forge sustainable habits for life. If you commit to practicing these consistently, then you’ll get the positive changes that you’re hoping for – not only in your body composition, but also your performance and overall health.

Sign up now for the Off-Season Body Composition Series, and we’ll send you the first class right away. You’ll then receive the remaining three over the coming weeks.

Disclaimer: The content in our blog articles provides generalized nutrition guidance. The information above may not apply to everyone. For personalized recommendations, please reach out to your sports dietitian. Individuals who may chose to implement nutrition changes agree that Featherstone Nutrition is not responsible for any injury, damage or loss related to those changes or participation.

Enjoying Holiday Foods Guilt-Free & Getting Back on Track After the Holidays

Enjoying Holiday Foods Guilt-Free and Getting Your Nutrition Back on Track Afterward

As the Andy Williams song reminds us, “It’s the most wonderful time of the year.” This sentiment should extend to the meals and snacks we share with family and friends, but for many people, the holidays may bring up feelings of guilt or shame around eating choices. In this week’s post, let’s explore how to positively change your attitude to season’s eatings and then take a healthy transition into the New Year.

Struggling with eating around the holidays? You aren't alone.

One of the reasons that Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Year’s, and all the time in between can become so tricky from an eating standpoint is that many people cut certain things out of their diet completely for most of the year. Then when the holidays roll around, it’s a free-for-all, as if they fear never having these “bad” things again once the season ends. So instead of incorporating favorites foods into their diet, they overindulge for a few weeks, which can lead to feelings of guilt during and after the holidays.

What’s a more constructive way to think?

Labeling foods or drinks as “good” or “bad” is subjective and not something that I recommend. While it’s true that some options are healthier than others, eating a little of most things is very unlikely to torpedo your overall health or performance, particularly if you maintain a balanced approach to eating well overall throughout the year.

At my house, we have a tradition of making frosted sugar cookies around the holidays. We eat a few, freeze some more, and relish every last bite. You should give yourself permission to enjoy whatever food-based traditions your family has created. If you’ve normalized these treats, then you won’t go through mental anguish, will savor the flavor and experience more, and won’t feel pushed to overeat something that you’ve labeled as forbidden.

What can I do to avoid overeating or binging?

One of the common challenges many people share about their holiday nutrition is sporadically going too far and over-consuming their festive favorites. When I dig a little deeper, I usually find out that this is preceded by them not eating enough or foregoing a meal altogether because they’re expecting to binge. Going too long without eating will inevitably compromise your willpower and planning to over consume will set you up to do just that. Even if a relative is planning a huge family feast at lunchtime, make sure that you eat a normal breakfast – because skipping that meal will leave you too hungry and more likely to overeat at your holiday gathering.

How else can I keep my nutrition steady through the holidays?

Another mental challenge that seasonal eating presents is that people can come to expect a drastic yo-yo effect every time Christmas approaches. First comes cramming cookies, cakes, and other sweet treats for a few weeks, quickly followed by rigid self-denial or cutting out certain types of foods (i.e. gluten, sugar, dairy, etc). This sharp contrast can create emotional & mental anguish, undermine positive habits you’ve spent all year building up and also mess with your hunger cues and metabolism.

Fortunately, it doesn’t have to be like that. If you can keep nailing the basics of nutrition that you normally stick to, you’ll have a much better holiday experience and avoid unnecessary upheaval. Tips for eating during the holiday season:

- Continue to eat 3 meals per day + snacks

- Stick to regular eating times, as much as possible

- Include carbohydrates, protein & fat at each meal

- Fuel before and after runs & workouts

- Don't let yourself get too hungry

- Give yourself permission to enjoy holiday foods

How can I incorporate holiday foods into my diet?

While your nutritional habits, routines, and structures can help you stay consistent, these don’t have to be overly rigorous. Give yourself a little grace and deliberately build in a bit of flexibility. One way to do this is to get creative with your eating before and after training. Instead of throwing down a couple of graham crackers or pieces of toast before heading out on a run, you could occasionally sub in a cookie or two (read more on why you shouldn’t be scared of carbs).

And after you’ve finished your training session, remember that you need post-run fuel. So as long as you’re including some post-workout protein – which could come from holiday meal leftovers like quiche – this could be another time where a holiday treat can come in handy to serve as your post-workout carbohydrates. Once you’ve changed your mindset, you should be able to fit these foods into a performance nutrition approach.

These are just examples of ways that you may choose to add holiday foods in, but there are no rules. Eat a piece of pie after dinner and eat a Christmas cookie (or more) with your children. Enjoy your time without stress around food.

What should I do if I eat too much?

This comes back to having the right perspective and allowing yourself a little latitude. Remember that you’re a person, not a robot, and accept that while it might make you feel overly full, one gigantic meal or snacking session isn’t the end of the world. If you eat too much one evening, don’t deny yourself breakfast or lunch the next day to try and compensate. Instead, just get back on track with your regular routine.

How should I approach eating in the New Year?

Once the celebrations are over, don’t get stuck in a cycle of regret and self-shaming. Instead, be honest with yourself about the practices that you might have drifted away from, and then return to them. Refocus on eating to fuel your performance and health, feel good, and power toward your goals. Get back to nutrition fundamentals, like planning three solid meals per day, adding healthful snacks as needed to support your activity level, and fueling before and after every run and strength session.

Disclaimer: The content in our blog articles provides generalized nutrition guidance. The information above may not apply to everyone. For personalized recommendations, please reach out to your sports dietitian. Individuals who may chose to implement nutrition changes agree that Featherstone Nutrition is not responsible for any injury, damage or loss related to those changes or participation.

Increasing Iron & Ferritin Levels Through Food & Supplements

Increasing Iron & Ferritin Levels Through Food & Supplements

In last week’s post, we shared how you can use blood testing to figure out whether your iron and ferritin levels are too low. If they are, this might be the cause or a contributing factor to feeling fatigued, heavy, and slow in training and other issues you’ve struggled to get to the root of. Now let’s explore how you can increase iron and ferritin through a combination of nutrition and supplements.

What should I do with my lab results?

Once you’ve gotten the blood panels we recommended, it’s helpful to work with a dietitian to interpret the results, look at the broader context of your training and lifestyle, and if you’re low in ferritin and iron, come up with a plan to remedy that. Getting the data is necessary but interpreting it the right way is even more important. This is important: We don’t ever want to blindly start an iron supplement – it can be dangerous if your iron levels get too high. I highly recommend consulting a dietitian or doctor prior to starting any iron supplement.

At what levels should I start increasing iron in my diet or supplementing?

As I wrote in part two of this series, the clinical range for an acceptable ferritin level is very broad – 10 – 120 ng/mL for women and 20 – 250 ng/mL for men. But from an endurance performance standpoint, the baseline should be 40 ng/mL, or 50 ng/mL if you live at high altitude or are planning to train in it. If your panels come back with lower numbers, it’s probably wise to start supplementing and getting more iron in your diet.

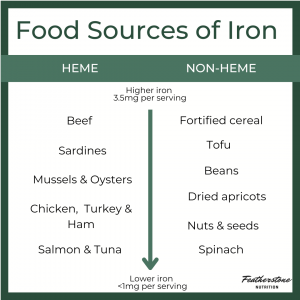

What foods contain iron?

There are two kinds of iron found in food.  Meat, fish, and other animal products contain heme iron, which is more readily absorbed. Solid sources include shellfish, beef, bison, lamb, turkey, ham, and eggs. Plant foods have non-heme iron instead, which is found in chard, kale, collard greens, spinach, broccoli, sweet potatoes, pumpkin seeds, brussels sprouts, nuts, lentils, and dark chocolate (bonus!). Fortified cereals and other foods also contain non-heme iron.

Meat, fish, and other animal products contain heme iron, which is more readily absorbed. Solid sources include shellfish, beef, bison, lamb, turkey, ham, and eggs. Plant foods have non-heme iron instead, which is found in chard, kale, collard greens, spinach, broccoli, sweet potatoes, pumpkin seeds, brussels sprouts, nuts, lentils, and dark chocolate (bonus!). Fortified cereals and other foods also contain non-heme iron.

What increases iron absorption?

There are some substances that can enhance the amount of iron you get from your diet. You’d do well to pair iron-rich foods with those that contain vitamin C, like peppers, citrus fruit, and kiwis because it increases absorption. Fermented products like kombucha, kimchi, and dill pickles also seem to increase iron uptake, as does alcohol. Another sneaky tactic is to use a cast iron skillet to cook with. A study conducted at Texas Tech University found that cooking spaghetti sauce in this kind of pan increased participants’ iron uptake by 2 mg, while they got 6 mg more from apple sauce.

What interferes with iron absorption?

Things that interfere with iron absorption include calcium, magnesium, zinc, soy protein, phytic acid found in some grains, nuts, and seeds, and, sadly for the caffeine crowd, tea and coffee. It doesn’t mean that you should avoid any of these – just try spreading them out a bit from your iron-rich meals.

Why might food not be enough?

As a registered dietitian, I always encourage clients to look to their nutrition first, if possible, and then utilize supplements. The recommended intake for iron is 8mg for men, 18mg for menstruating women, 27mg for pregnant women, and 8mg for post-menopausal women. So, as you can see, many women need several to many high iron foods per day, which is difficult for many people to consume. There’s another challenge, in that your body can only absorb 15 – 35% heme iron from animal sources, and just 10 – 15% of non-heme iron from plant-based foods. That’s why you may need to pair iron-rich nutrition with supplementation to get your ferritin and iron up.

Other reasons food alone may not be enough include if you’re extremely low in ferritin and iron, are training hard, are planning to train or race at altitude, or have a lot of extra life stress. If you’re vegetarian or vegan, you may need a supplement because the iron you’re getting from non-heme foods probably isn’t sufficient.

What are the best practices for supplements?

There’s a pretty broad range of potency with iron supplements, from 20 to 85 mg or more. How much you take depends upon what your diet looks like and how low your levels are. As with most supplements, it’s best to start with a low to moderate dosage and then build up from there if needed. A review out of Cornell University found that supplementing with just 20 mg a day increased iron stores, leading to improved performance and health outcomes.

In terms of timing, one hour before a meal or two hours afterward seems to be a sweet spot. A study published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise found that if you run in the morning, taking your iron supplement afterward will increase iron absorption. Like I advised for food-based iron, avoid taking your iron supplement with others that contain magnesium, calcium, or zinc, as it will reduce absorption. This is why a standalone iron supplement is better than a multi from an iron perspective. Conversely, if you take vitamin C, you could do so with iron to increase absorption.

There can be side effects from taking iron – most typically constipation and GI distress. If you struggle with these, then cut back your intake or split it into two at different times of day. As heme iron is better absorbed, you might be able to take a lower dose of it than you would with the non-heme kind. Some supplements have a combination of both, and others are slow release, which can be gentler on your stomach. You can check out some of the products I use and recommend here.

How long will it take to notice a difference after starting a supplement?

People can start to notice positive changes with certain supplements like vitamin B12 almost right away. But iron stores take longer to increase, so don’t expect a “wow” factor after a day or two. Consistent daily iron supplementation should start to make a difference in about two weeks, and a month in, you may observe noticeable impact on your performance and recovery. However, for some people, it will take months for ferritin levels to increase, so be consistent & patient.

Do you need an expert to interpret your labs? The Featherstone Lab Consult is now available!

1. YJ Cheng and HC Brittin, “Iron in Food: Effect of Continued Use of iron Cookware,” Journal of Food Science, March 1991, available online at https://ift.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2621.1991.tb05331.x. 2. Diane M DellaValle, “Iron Supplementation for Female Athletes: Effects on Iron Status and Performance Outcomes,” Current Sports Medicine Reports, July-August 2013, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23851410. 3.Rachel McCormick et al, “The Impact of Morning versus Afternoon Exercise on Iron Absorption in Athletes,” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, October 2019, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31058762.

Disclaimer: The content in our blog articles provides generalized nutrition guidance. The information above may not apply to everyone. For personalized recommendations, please reach out to your sports dietitian. Individuals who may chose to implement nutrition changes agree that Featherstone Nutrition is not responsible for any injury, damage or loss related to those changes or participation.